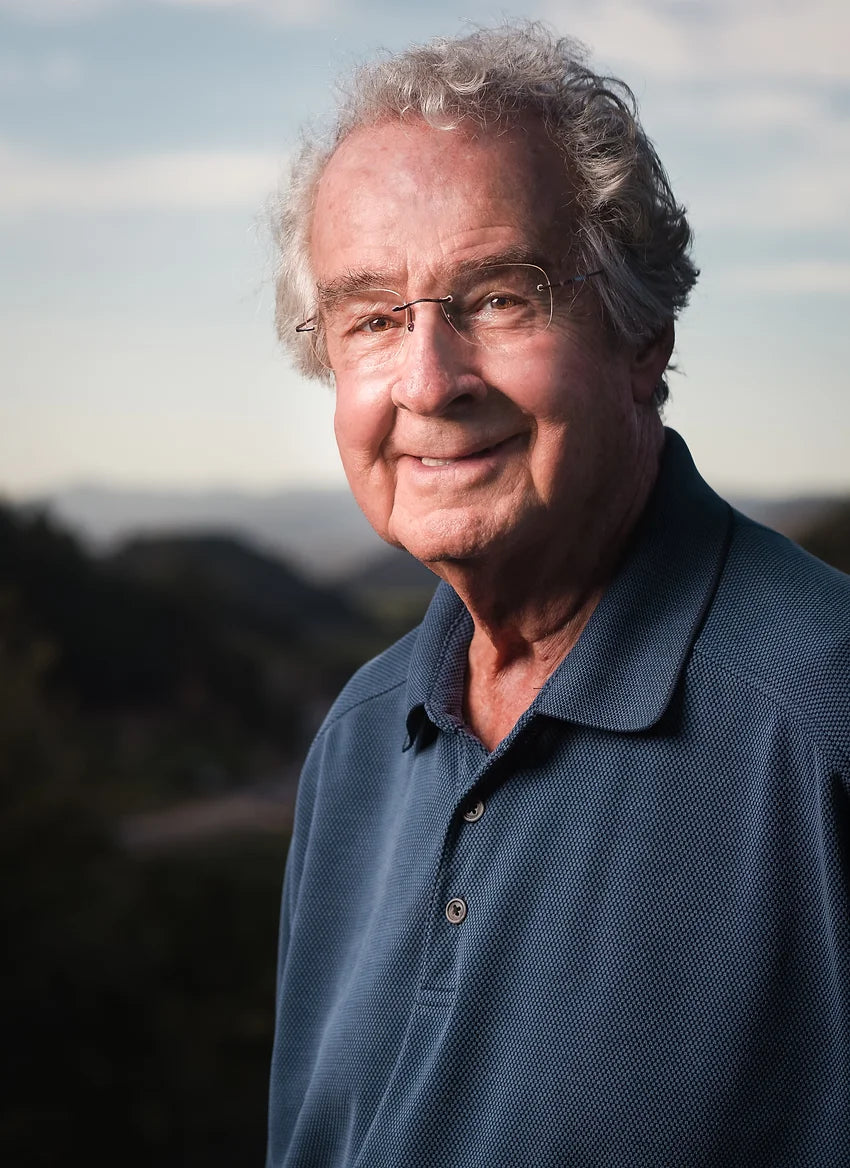

One of the great privileges of publishing wine books is that we are sometimes able to meet extraordinary people. Warren Winiarski, who died at home in Napa last week at the age of 95, was one of those giants of the industry who several of us at Académie du Vin Library were lucky enough to work with.

This was largely due to the event that probably most defined Warren’s life. His 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon was the winning wine in the 1976 blind tasting which came to be known as the Judgement of Paris, organised by our late founder Steven Spurrier, beginning a friendship that would last until Steven’s death in 2021.

Warren generously supported the publication of our title, On California, and he also funded the Spurrier-Winiarski Writer-in-Residence award with UC Davis, one of his many philanthropic activities. He also gave a significant endowment to the university’s Library, enabling them to create the world’s largest wine library with papers from Hugh Johnson, Jancis Robinson and Steven Spurrier amongst many others.

Warren was far more than the winner of that extraordinary competition however. A lecturer in political theory at the University of Chicago, he experienced a damascene moment in Italy while studying Machiavelli and knew he had to become a winemaker. He and his wife Barbara moved to California in 1964 and he soon became the first winemaker at Robert Mondavi’s winery. Before setting up Stag’s Leap in Napa Valley he also helped found the wine industry in Colorado at Ivancie Cellars making wines from California grapes. He would continue to support Colorado’s emergence as a wine region throughout his life.

He had a reputation as one of the thinkers of the wine industry, and he never lost his intellectual curiosity. This drove him to support budding wine academics and also to initiate The Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History's American Food & Wine History Project. The project uses food and wine history as a lens for understanding American history by tracing the long and diverse history of wine in the United States. We saw his keen intellect when he took part in a webinar to celebrate the launch of On California. He was in serious company – Hugh Johnson, Karen MacNeil and Elaine Chukan Brown to name just three of the panellists – and at 93 years old he had lost none of his gift for asking the insightful question.

Warren will be much missed by his colleagues in Napa Valley, for whom he spearheaded the Californian Conjunctive Labeling Law that required every bottle of Napa Valley wine to include the region on the label, cementing the Napa brand as one of the world’s important wine regions. He sold Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars for $185 million in 2007 to Canada’s Ste Michelle and Marchese Piero Antinori, but continued to grow grapes at his beloved Arcadia vineyard, while also focusing on philanthropy, teaching and conservation. His wife Barbara pre-deceased him but he leaves three children and six grandchildren.

Adam Lechmere adds:

Warren was a brilliant winemaker but he also understood one of the prime rules of marketing: meet your public. He was an indefatigable traveller, circling the globe to put his wines in front of people, and to explain, in his patient and slightly didactic manner, why they rivalled and even bettered the greatest wines of Bordeaux.

I met him many times, in London; over lunch in Napa, often at Don Giovanni, his favourite restaurant a stone’s throw from the winery he founded, and at his fine hilltop house (complete with high-spec telescope) above the vineyards, where he ended his days. He was good company, though he never forgot he was talking to a journalist. Just as you were tucking into your burrata he would put his hand impressively on your arm to make a point about the primacy of the Stags Leap terroir.

About 15 years ago, when I was in Napa to interview Francis Ford Coppola at Inglenook, I had lunch with Warren. We chatted about the director – he was a huge fan of what Coppola had done to revive the great old winery. Later that evening the phone rang in my hotel room and Warren’s precise, mid-Western tones came down the line. “I’ve been thinking about what we talked about,” he said. Just in case I hadn’t got it the first time, he underlined comments he’d made at lunch, about the “high-minded, noble enterprise” that he considered Coppola had undertaken.

High-minded is an apt description of Warren himself. Even on a tractor he had an intellectual air. There’s a famous picture of him on a Massey-Ferguson planting his first vines. In his spectacles and concentrating on the rows, he still looks like the academic he recently was. He was a complex character – in the decade after the sale of the winery, he was very much a presence in Stags Leap. We did a big restrospective in 2020 at Club Oenologique, and it was made very clear to me that Warren should not be mentioned by name. “He wants simply to be known as ‘The Founder’”, I was told.

Above all, he was a gentle, intelligent and kind man who saw the promotion of Napa – and of Stags Leap District – as his life’s mission. Of course he took things seriously, and if he never let anyone forget the pivotal role he played in the Paris Tasting and in the creation of Napa, well, there was no one who had more right to claim that crown.