I am writing this as a long, low ray of golden sunshine illuminates Le Pin and the russet red sarments that are still standing to attention, supported by the taut trellising wires in disciplined rows, their architecture accentuated by the lack of leaves. This is a time of year when days like these are to be treasured; winter sunshine is a precious gift – it warms our bodies and our souls and, in a few weeks, we will need it even more.

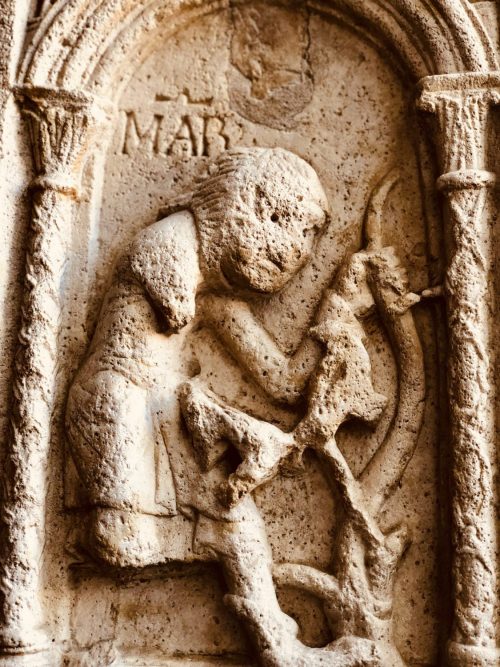

It’s almost pruning time. We like to wait until the first frost has arrived, driving the sap and final juices back down the trunks of the vines to the roots where their energy and memory will hibernate, protected by the banked-up soil that surrounds their feet. Do vines have memories? Do trees talk? The vines seem to sway, carrying still the memory of the last harvest captured in the lattice of their twigs. However romantic our notions are on this subject, there is more and more evidence that plants talk to each other. The vines seem tired but happy; ready to hunker down for the winter and appreciative of these last attentions that we are about to lavish on them. Read Richard Powers’ The Overstory and you might catch a whisper of what they are saying to each other.

If you have never pruned a vine, then you have never really felt the importance of this plant. I realized that having a go at pruning was going to be essential when I was studying for the Master of Wine exam. How could I possibly explain different pruning methods, if I had not done it myself. It would be like writing a recipe with an ingredient you had never tasted. Easier said than done since I was living and working in New York City at the time. So, during several Saturdays I would take the train eastwards to the North Fork of Long Island to prune vines out by the Hamptons, somewhat sheltered from the winter chill by the warm currents of the Sound.

Seasoned hands prune instinctively, automatically but for beginners like me, I had to study the architecture, pick out the nodes, trace the lines that the sap was taking and then hesitantly make the cut. Snap. A sound that still brings a whiff of terror with it. With pneumatic pruning shears that everyone now uses, that snap could quite easily be a finger rather than a nub of dead wood. Shudder the thought.

Depending on the weather, pruning can be uplifting or soul destroying. Beautiful sunlight like today can raise spirits, widen the horizon, lift your gaze over fields of serried vines and toast your back. Dull wet days with heavy clouds scudding low and raindrops drizzling down your neck can cause you to bow your head to the height of the plant as you try to find some shelter amongst the forest of trunks.

This is one of the least understood and most important acts in the vines’ life. The talented Italian viticulturist, Marco Simonit has turned it into an art; preaching the gospel of driving the vine’s energy to its extremities by making sure that the pruning cuts and scars do not block the sap. Where we have the space, we are opening up the vine so that its arms are stretched wide instead of one simple limb. This reduces the build-up of sugar that we mistrust and dislike and balances the plant’s energy at this time of global warming. We have made the vine strong and ready for the growing season ahead, whatever the vagaries of the climate change throw at it.