Wild yeast means complexity and terroir influence, cultured yeast means bland and formulaic wines – or so the thinking goes. But it’s a whole lot more complicated than that, says Natasha Hughes MW

The headline might sound like the tagline for a low-budget horror film, but actually it’s a simple statement of fact about yeasts. Anyone who has made sourdough bread will be aware that you can (usually) create a seething, bubbling starter culture by mixing flour and water in a jar and leaving it in a quiet corner of your kitchen for your household yeasts to get to work.

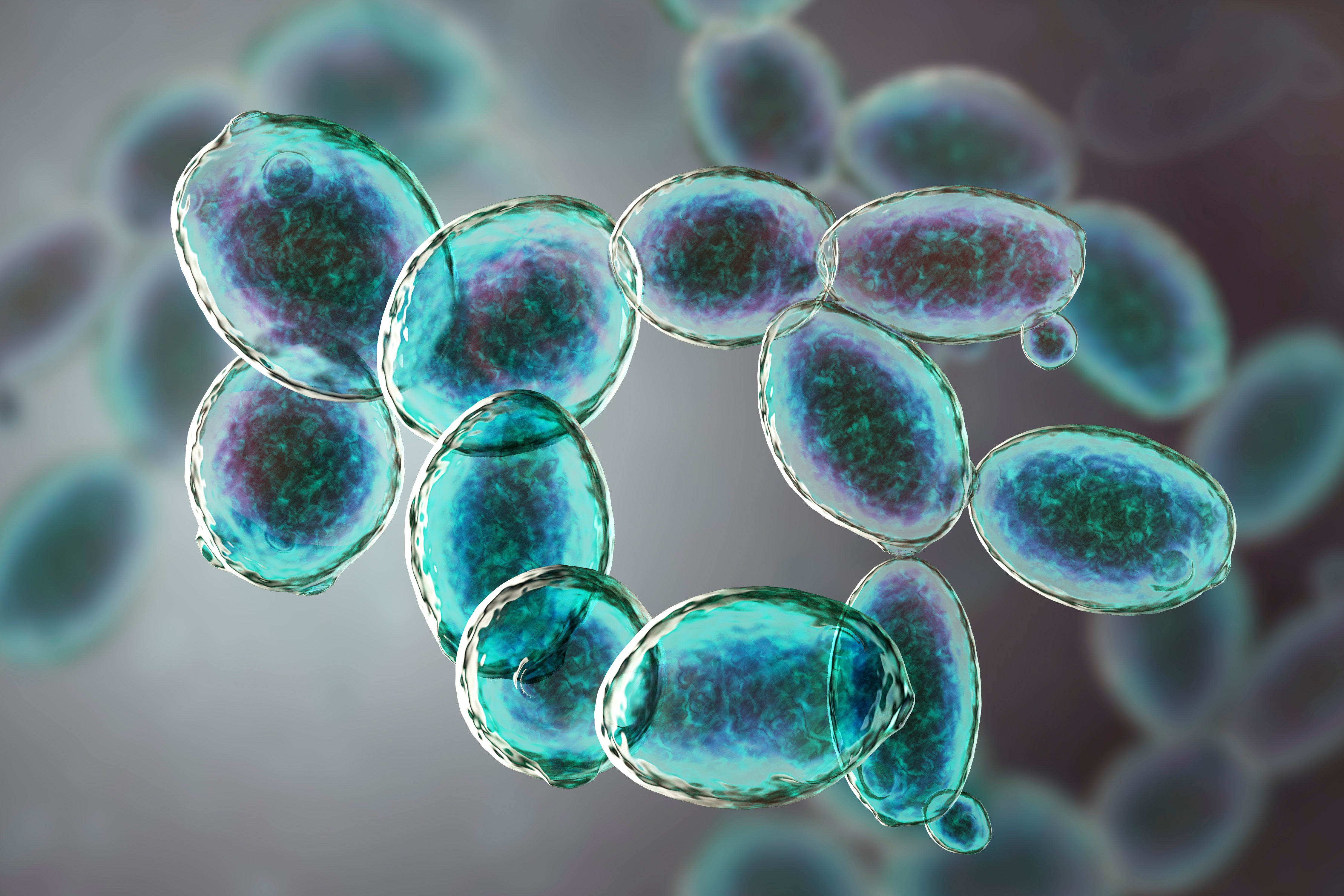

If you were to analyse the many species of yeast that bring your sourdough to life there’s a good bet that you’d find a healthy population of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a species familiar to winemakers around the world. (When you think of a yeast species like S cerevisiae you need to do so in the same way as you think about Canis familiaris: a dog is a dog, regardless of whether it’s a greyhound or a chihuahua. Similarly, there are lots of ‘flavours’ of S cerevisiae out there.)

Across the world, many winemakers use cultured wine yeasts – bought ‘off the peg’ and usually employed to create specific characters in the finished wine. Most of these are based on S cerevisiae, but the end result they achieve varies, depending on the strain. Winemakers use 71B, for instance, to create wines whose aromatic profiles are dominated by fruity esters (think slightly confected strawberries and bananas), while QA23 is typically used to express a tropical fruit character in Sauvignon Blanc. Cultured yeasts aren’t always employed to create a suite of aromatic characters either – speedy fermentation might be the goal, or the ability to ferment at cooler temperatures than usual. Each yeast has its own individual superpower.

But while cultured yeasts are widely used to achieve specific winemaking goals, some winemakers, like Domaine Leflaive in Burgundy and Ridge Vineyards in California, turn to indigenous yeasts to guide their fermentations (a technique sometimes known as spontaneous or wild fermentation). Instead of sprinkling a single strain of proprietary yeast into their vats, the idea here is to let the ambient yeasts that live on the skins of the grapes and the walls of the wineries (and the insides of the tanks, and pretty much any available surface) rip.

Many of these yeasts are not Saccharomyces species – or even members of the Saccharomyces genus – there’s a whole microbiological gamut out there, including Hansenula, Kloeckera, Candida and Pichia. The idea is that different kinds of yeasts are active at different phases of the fermentation, and each of them give rise to a specific suite of characters before dying back to make way for a different yeast, creating complexity in the finished wine.

But spontaneous fermentation can be risky. If the wrong kind of yeast takes the lead in the fermentation relay, all kinds of unwanted aromatic by-products can be expressed. An example of this might be Brettanomyces, aka ‘brett’, a species of yeast whose domination of a ferment can result in the creation of an array of undesirable aromas, from cloves and smoke to mouse droppings and sweaty saddles. Having said that, some people are not averse to a little bit of brett in their wine, finding that, in judicious amounts, it can add an element of savoury complexity. Alternately, the fermentation might grind to a complete halt, leaving residual sugar in a wine that was meant to be dry, and creating a breeding ground for acetobacter (an organism that creates unpleasantly high levels of volatile acidity) and a serious risk of refermentation in bottle.

Nevertheless, many winemakers believe that wild fermentation is worth the (calculated) risk for the sake of increased complexity in their wine. The suggestion that indigenous yeasts can contribute to the terroir character of a wine is an additional incentive for many. Research cited by Hervé Alexandre, Professor of Microbiology and Oenology at the University of Burgundy, in a recent seminar on yeast and terroir points to links between different yeast populations in different geographical locations in vineyards, which initially seems to support the concept of microbial terroir. However, Alexandre also points out that the yeasts that are carried into a winery on the skins of the grapes are typically not the ones present in the must after the grapes are crushed, so the terroir being expressed in the wine may well be a reflection of the winery’s microbiome rather than that of the vineyards. The clue that this may well be the case is that wineries can find it difficult to get indigenous fermentations going in newly built wineries that haven’t yet had time to build up their population of yeast species.

One further twist to the tale is that the notion that cultured yeasts typically produce wines of monolithic consistency is a false dichotomy, according to Ann Dumont, a microbiologist who works for Lallemand (one of the world’s biggest suppliers of yeast to the brewing and wine industry). She says that, with the exception of strains deliberately used to initiate rapid fermentation, there’s a lag phase between inoculation and the point at which S cerevisiae comes to dominate the fermentation process. This gap allows a whole suite of winery yeasts to be active in the must. Under these circumstances, S cerevisiae is there to clinch the deal and ensure that fermentation rolls smoothly towards its conclusion, while allowing other yeasts to have a voice in determining the character of the wine.

The more closely you examine the arguments, the more apparent it becomes that a simple binary proposition that creates a clear-cut opposition between cultured yeasts and indigenous yeasts is really a Just-So story. The truth is out there somewhere, just like all those yeasts.

Natasha Hughes graduated as a Master of Wine in 2014, winning several prizes as she did so, including that year’s Outstanding Achievement Award. For the past 20 years she’s freelanced as a journalist and educator, specializing in wine and food. She also consults for private clients, wine producers and restaurants, and is currently researching her first solo book on the wines of Beaujolais. You can follow her on Instagram @latashmw