‘Wine is not human life, but it is real life all the same.’ - Serge Hochar

Chateau Musar, The Story of a Wine Icon

Serge Hochar’s skills as a winemaker were legendary. He not only crafted wines under the most difficult wartime conditions imaginable (bullets and bombs pelting his Beirut office, roadblocks and rockets making the roads he travelled impassable), but his approach to their ‘upbringing’ was entirely unique. For Serge, his wines were more than just his creations, they were his salvation; he’d say: ‘Wine is my friend, companion, medicine, advisor and doctor.’

Serge had been an inquisitive child, with a bunch of existential questions, beginning with ‘why am I here?’, that refused to be solved. According to Andrew Jefford (who interviewed him in 2004), Serge worked on solving his conundrums from the age of about seven to 15, and then gave up. ‘I couldn’t understand why I was alive,’ he said.

But then he made a discovery. Wine. ‘Wine was a very satisfactory answer to my question. It was indirectly an answer to the mystery of existence. It made me accept life. Wine is not human life, but it is real life all the same.’

Not everything Serge said made immediate sense to those who listened. Even as he spoke them, his elliptical pronouncements appeared to strive towards an evasive truth. But often enough, given time and focus, they’d provide gold-nugget revelations about wine and about life. Wine helped Serge express his philosophy – it was his philosophy.

This wasn’t just because wine had been embedded in his country’s history since Phoenician times. A symbol of prosperity and well-being, a stimulant of music and the arts, a religious tribute, a social lubricant and even a solvent for dispensing medicine. It was a ‘live’ and changing product that would evolve in accordance with the temperature of the earth, the sunlight and rain that fell on the grapes. Its very nature also depended on the ease (or otherwise, given the bombing) of its journey to the winery and the emotions felt by the winemaker as he planned its ‘schooling’ through fermentation to its sojourn in Nevers oak barrels. Wine had its own life, and – for Serge – it reacted to, and evolved with the lives going on around it.

By the time of Lebanon’s Civil War (1975 to 1990), Serge had gained a deep confidence in his ability to make wine – specifically Lebanese wine that reflected the terroir of the Beka’a Valley and the ‘feeling’ of his homeland. Key to this was his ‘No Touch Policy’. He had learned that the less he intervened in the winery, the more genuine, intriguing and generously long-lived his wine would be. One of his more revealing ‘Serge-isms’ ran:

‘It can be tempting for a winemaker to interfere with the life of his or her wines. It can be tempting to treat a wine with interventions that make it more stable, or better behaved. But the only intervention I trust is trust. I will not strip anything out of my wines. I know that most winemakers filter their wines, and I have nothing to say for or against them: I can only speak of my wines. For me, the organic matter, those billions of tiny particles in a bottle of my wine, that is the brain of the wine. That is what allows the wine to mature, to be intelligent. If you strip out this organic matter, then (in my opinion) you lobotomize the wine. The wine may be stable, but it will not evolve in an interesting way.’

Inevitably, there were times during the war that Serge became trapped – either in the winery cellars with his loyal staff, or (infinitely more dangerously) at his top-floor apartment in Beirut. With shelling and gunfire all around, he would reach for one of his wines and pour it. Then, in a form of meditation, he would encourage those around him to ‘take a sip, just a tiny sip’, and ‘listen to what it is saying’. He said of an experience in early 1990: ‘Each time a shell landed, I would take a sip and ask the wine, “What do you have to say to me now?” And the wine would talk to me. It would tell me its memories about soil and sunlight and the taste of water. It could remember these things! It remembered all of history!’ (Quoted from an article by Elizabeth Gilbert, ‘A Wine Worth Fighting For’ in GQ magazine, September 2004, and reprinted in our book, Chateau Musar, with her kind permission.)

This was a deeply immersive, calming encounter that Serge encouraged others to experience too. He travelled widely to meet with sommeliers and wine lovers in the United States, to conduct tastings in the Far East, to Brazil (with its sizeable Lebanese population) to give wine lectures, or to attend the grand wine fairs of Europe. And everywhere he went his message about Chateau Musar was the same: ‘My wines are natural, I am the one who makes them, but I do interfere with nature. Taste them and listen to them and you will see!’

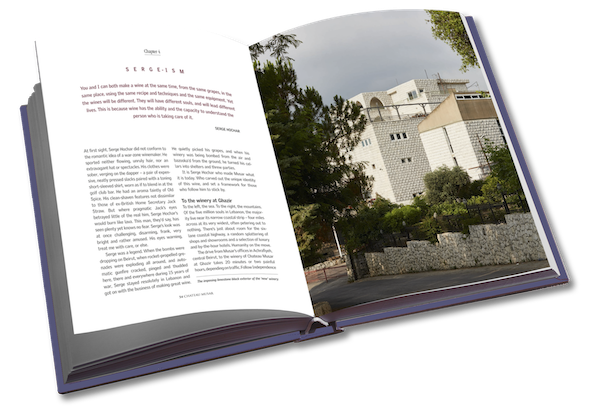

Learn more about Serge and his wines, their terroir, their history, their survival and the multi-faceted, changing characters of vintages from 1951 to the latest release (all described by Steven Spurrier, Jancis Robinson MW, Michael and Bartholomew Broadbent) in our new book: Chateau Musar, The Story of a Wine Icon.

2005 ‘A Cabernet vintage – not pretentious or aggressive. Une profondeur interessante. It is powerful, but this wine is still young, a baby.’ (Serge Hochar)

Full garnet-red colour, mature. Red and black autumn berries on the nose, smooth and ripe with an appealing warmth, cinnamon and figs; the spicy fruit from the Carignan grape adds a savoury smoothness to the firmer Cabernet. Tannins are resolved, mature, while the Musar acidity keeps the finish fresh. A fine, open wine, seemingly at its peak now, but one can never really know with Musar. To 2025. 17.25 (Steven Spurrier)

Buy here

1995 ‘A great year, great weather. Mid-summer heat with lots of sunshine and cloudy evenings. Perfect. The grapes came in at full maturity but some did not finish their fermentations; these were racked (pumped into different vats) but not sulphured – this was because of my No Touch Philosophy. It took some grapes one year to ferment! The volatile acidity went up, of course. We bottled it in 1998, but when we wanted to release it in 2002 it was too acetic, not ready. So we released it alongside the 1996. Now, people tell me it is my greatest vintage.’ (Serge Hochar)

Mid to deep red, tawny rim. Good for its age. Attractive autumnal berry fruits on the nose and natural warmth still present with lifted, elegantly textured fruit and good length on the palate. Still firm, with a clarity of expression that will remain for another few years. To 2025. 17.5 (Steven Spurrier)

Buy here

1977 ‘An important year because I settled on the Chateau Musar recipe: more or less equal quantities of Carignan, Cinsault and Cabernet Sauvignon.’ (Serge Hochar)

Sweet, assertive, still tannic (July 1999); singed flavour, long tannic finish (December 1999). Sweet, rich, fairly full-bodied despite misleadingly pale colour (April 2000, four stars). (Michael Broadbent). Mahogany-red, tawny rim, still with some vigour but fading. Surprising freshness and natural richness on the nose, not the depth of 1981 nor 1979 but Mediterranean warmth is plainly there in a slightly leaner form. What other half bottle today could show such warmth, clarity and sense of place after 42 years? 17.5 (Steven Spurrier)

Buy here